Orbis leads the global fight against blindness, bringing care to communities around the world

From the moment we open our eyes each morning, we are reminded how important and wonderful it is to be able to see.

The alarm clock may not be anyone’s favorite sight on a workday, but the faces of loved ones are, as is a clear, sunny sky. Then there are the more practical aspects of eyesight, such as getting dressed, fixing food, finding your way to work or school, and the endless list of other daily events we navigate by sight.

For some people, gazing at a sunset or staring at a computer screen is often taken for granted. And if vision problems arise, contact lenses or laser surgery are readily available if glasses don’t seem a stylish enough solution.

Yet in many parts of the world, basic vision care is not widely available or is a luxury most people can’t afford. These barriers contribute to more than 250 million people worldwide dealing with blindness or severely impaired vision. What makes that number all the more tragic is that 75% of cases could be prevented or treated, according to Orbis International, one of the world’s leaders in fighting blindness.

For almost 40 years, Orbis International has worked to provide people in developing countries with the gift of sight. Orbis addresses this problem through a range of programs, most importantly training medical personnel in developing countries, both in person and online. This training provides up-to-date treatment where it is needed most. Orbis also organizes clinics around the world staffed by volunteer doctors who provide both much needed treatment and the chance for local personnel to observe procedures in person.

The impact of this training and care is staggering. In the past five years alone, they include more than:

- 174,000 trainings of medical personnel

- 15.7 million eye screenings and examinations, 11 million of these on children

- 386,000 eye surgeries/laser procedures

- 28.6 million medical/optical treatments.

While helping a person see is an important enough achievement, the economic impact is even greater. Each person helped by Orbis is someone who can still work and help their local community. Price Waterhouse estimates that for every dollar invested in eye health, there is an economic gain of $4.

“We invest in preventing blindness, and the return is huge, not just to the individual, but also to the community and the local economy,” said Louise Harris, chief of communications and marketing for Orbis.

Ethiopia offers an example of the local impact of Orbis. In Ethiopia, more than 1.6 million people are blind and another 3.8 million suffer from low vision. Orbis opened its first program office there in 1998 and since then has helped open almost 300 eye care units or centers, conducted 2.25 million eye screenings or examinations, almost 25 million optical treatments and more than 170,000 eye surgeries. Even more, Orbis has completed more than 77,000 trainings of local eye care professionals, helping Ethiopia strengthen its own capabilities.

Orbis’s key asset is the more than 400 volunteer faculty members who conduct many of the training sessions and perform examinations and surgeries in places where their expertise is needed. These volunteers include many professors from leading medical schools, providing Orbis with not just skilled physicians, but the world’s true experts.

The internet has greatly helped this faculty’s ability to provide training around the world. Through Cybersight, volunteers such as Dr. Daniel Neely can train and mentor doctors around the world, helping them get the skills they need to address vision problems in their local communities.

Lenovo supports Orbis through technology donations, notably with equipment for the Cybersight program. By providing state-of-the-art monitors and cameras, remote training and collaboration is both easier and more effective.

“You don’t read a book and become an expert,” Neely said. “Cybersight allows doctors to connect with a truly global network of professionals.” (Neely, a professor of Ophthalmology at the Indiana University School of Medicine, discusses Cybersight in more detail here.)

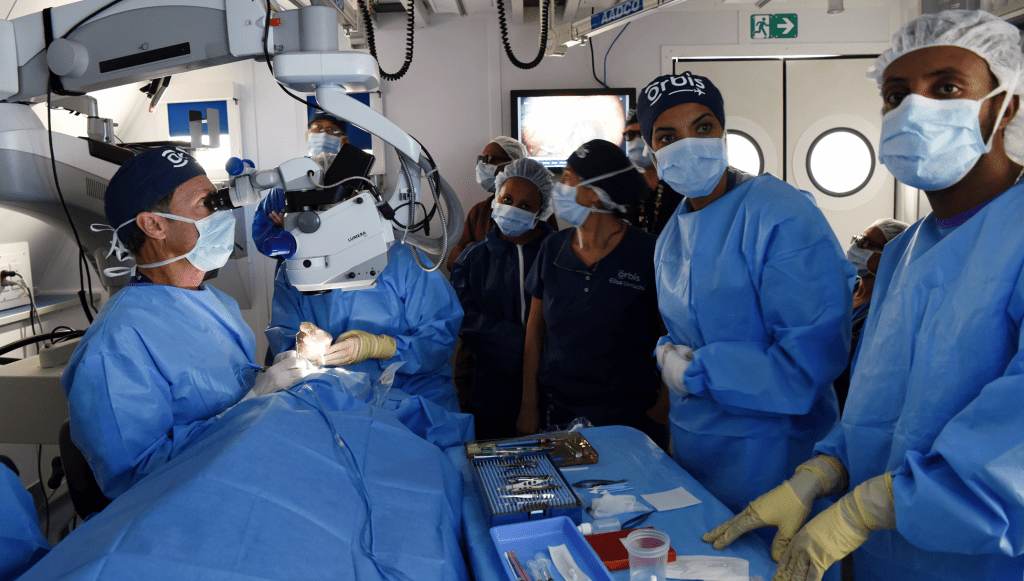

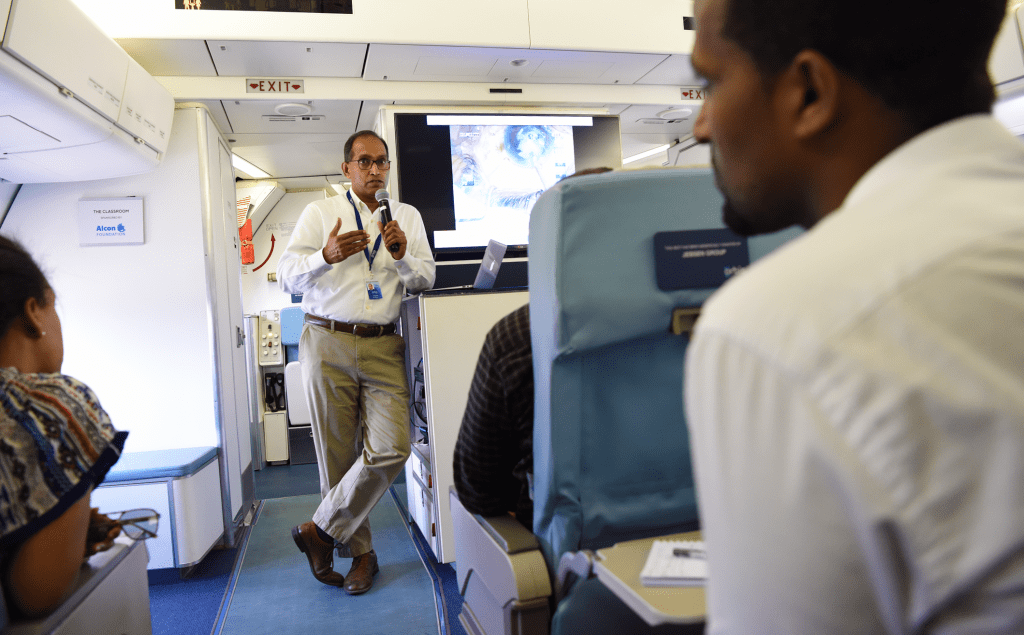

The volunteer faculty also conduct much-needed clinics in every corner of the globe, often with help from the Flying Eye Hospital, Orbis’ MD-10 airplane equipped with facilities for surgery and training. This state-of-the art mobile hospital allows Orbis to bring its world-class volunteer doctors to remote locations to conduct eye screenings, treatments, and even surgeries, all while allowing local medical professionals to observe and learn these same procedures.

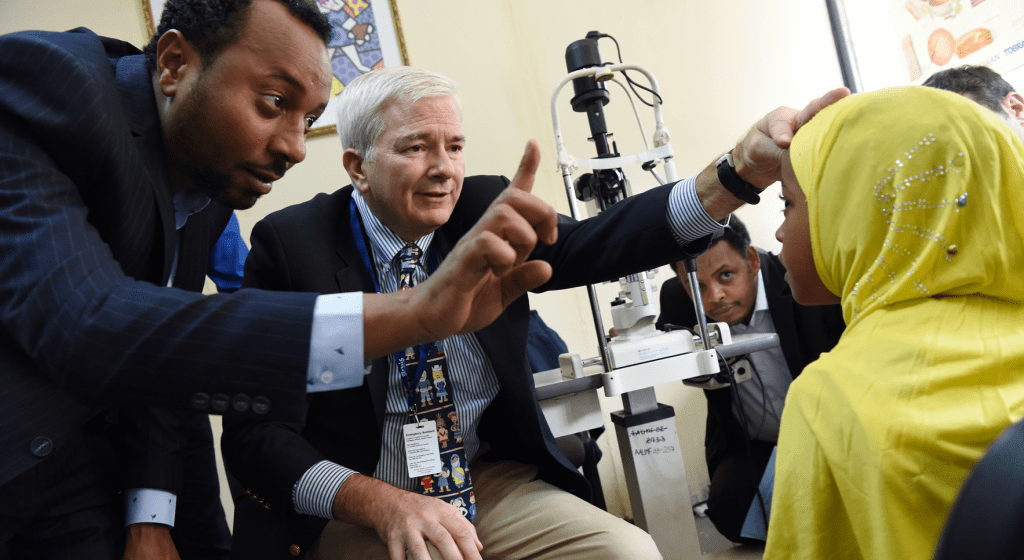

Dr. Douglas Fredrick has been traveling to conduct such clinics for 20 years. His day job is professor of ophthalmology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai/New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, yet he finds great satisfaction and meaning in the impact of the training programs he works on through Orbis. (Fredrick also makes an appearance in this trailer for a film about Orbis hosted by Cindy Crawford.)

“You know the skills you are helping to provide will be multiplied many fold,” Fredrick said. “The people you work with will then bring that same level of care to hundreds of people over the course of their careers. And I am proud of how Orbis is really diligent in following up three months after any surgery to ensure everything went well.”

Fredrick took his first trip with Orbis in 1998, going to a hospital in Yangoon, Myanmar, to teach a special course on treating infants and children with cataracts, a more specialized procedure than cataracts in adults. His first patient, a child with Down syndrome and cataracts, was known at the program as “Green Pants,” as he always had a pair of green trousers. Fredrick performed the surgery, which he thought went well, and then, when the program was over, went home.

“The following year I went back to Yangoon with Orbis,” he said. “Usually we don’t see any of the same people more than once because many come hundreds of miles to attend a clinic. But in this case, his father brought Green Pants back, and he was running around playing, in thick glasses, but seeing just fine. The father was a wood carver, and he made a statuette of a hand cradling an eye. He gave it to me and said this was his baby’s eye and this is your hand saving my baby’s eye. That really put the hook in deep, and Orbis has been an important part of my life ever since.”

Want to help? Learn more about Orbis International here.